|

Home

Historical Research POW

Evasion

Reports

Français

|

Ossian Arthur Seipel's Memoirs

Previous

Chapter 5

The March

Center compound was the last to leave.

As we passed the north compound you could

see a number of barracks burning. It’s

surprising that there weren’t more fires. |

|

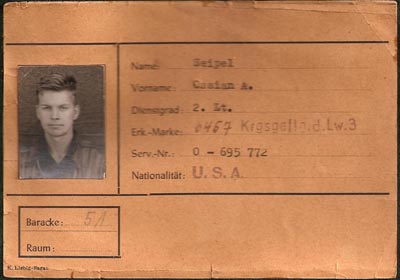

2nd Lt Ossian

Arthur Seipel's ID issued by the German - Photo Lynn Dobyanski |

We

were lucky to be the last to leave ‘cause the

thousands of feet ahead of us had trampled the snow

pretty well and the going wasn’t too bad. It was

cold though, close to zero. We marched for about an

hour and a half then rested for ten minutes and then

resumed the march. Many refugees fleeing from the

Russians kept pace with us, following a short

distance behind, taking advantage of the packed

snow. They were a miserable bunch, trying to take

as much of their belongings as they could. Some had

horse drawn wagons loaded down with furniture. The

small children rode on the wagons too. They finally

turned due west while we continued in a

southwesterly direction

We encountered a lot of German soldiers taking

defensive positions along the side of the road,

dressed in their camouflage snow suits, armed with

bazooka type anti tank missiles and machine guns.

They ranged in age from early teens to well into

their sixties. The Germans were scraping the bottom

of their reserve forces. We thought there might be

a slim chance that we’d be overtaken by the oncoming

Russians and our spirits rose a little. Just being

outside of the fence was enough to make a guy happy,

but before noon we realized that our existence

depended a great deal on the whim of the Germans.

Popeye, the one-eyed German sergeant along with

Colonel Spivey had a time keeping the men from lying

down during our rest stops. It soon became apparent

that the ones who kept moving were better off than

those who laid down. Those who did lie down soon

got stiff and sore and required assistance from

their combine mates. Fortunately our combine was

OK.

The cold continued and more snow fell until we

stopped in Halbe, a town of about 40,000 people. We

stood around while Popeye and the German major found

us a place in a big church where we could get out of

the wind. The church was heated so we were really

in luck. Only about 900 men could cram into the

church. General Vanaman stretched out on the altar

and the rest of us in the church crowded together in

the pews, on the stairs and in the aisles. There

was no room to lay down, but as long as it was warm

we managed to sleep sitting up. About 1200 guys who

couldn’t get into the church were finally allowed

into a parochial school next to the church. I think

they had it better than we did in the church. They

could at least lie down.

Next morning we were roused out by the guards

and after a long and mixed up attempt at appel we

were on the move again. By this time we discovered

those ferrets and guards that we joked with and

about at Sagan, could speak English as well as, if

not better than most of us. One had been living in

Chicago and attended Northwestern University, until

Germany marched into Poland. Another one had

studied at Oxford in England until he was called

home to Germany because of the war.

It was still bitter cold and the wind continued

to blow. Fortunately the snow had stopped. We

continued the one or two hour march and ten minute

rest until about two PM when we stopped in the lee

of a fairly dense woods for our lunch break. Twigs

from the trees made enough fires to warm us pretty

well until we had to leave. By nightfall we reached

our destination for the night. It was a huge farm

run by a German Count and his hundreds of slave

laborers. We were allowed to stay in three big

barns filled with hay. The only condition as

stipulated by everyone with any sense was, “No

Smoking”.

Some of the kriegies knew how to speak Polish

and were able to buy potatoes from the Polish

laborers. Eight potatoes for a real bash. Tom

Ledgerwood and I kept the fire going while Ted

Snyder fried up some Spam and potatoes. Somebody

else got some eggs for a couple of chocolate bars

and Ted scrambled them too. It wasn’t much, but it

was the best meal we had had in a long time.

Sleeping was no problem. When you wrapped your

blanket around your body and burrowed deep into the

hay it was almost warm. Some of the guys took off

their shoes and by morning they were frozen stiff

and difficult to get on again. Colonel Spivey

talked Popeye into letting us staying there, under

guard, another day while he and some of his men

found shelter for the next night. We spent the day

resting up and trying to get our clothes dry.

They roused us out at dawn the next day, the

fourth day of the march, and we were under way with

out the coffee that they promised us. It was still

bitterly cold and the wind in your face brought

tears to your eyes. We were heading in a

northwesterly direction now. Everyone seemed pretty

down and grouchy as the morning wore on. Some of

the guys who still carried large packs got so tired

that they couldn’t keep up and were threatened with

execution on the spot. Needless to say they

unloaded some of their packs and went on. By

evening we were dragging pretty much. Most of us

were in a sort of daze, not talking just taking one

step at a time behind the guy in front. Maybe we

even slept on our feet. I can remember running

smack into the back of Knox, who was ahead of me

when he stopped and I didn’t. About dusk we arrived

at Muskau, which was about 50 kilometers from the

farm we stayed at the past two days.

Center compound had been assigned to stay in a

huge pottery plant. Our block was to sleep on the

second floor over the ovens. It was hot and we

welcomed the heat. We discovered that there were

concrete plugs in the floor spaced evenly across the

area. The plugs had iron rings on top and if you

lifted them out of the holes you had a hot flame to

cook on. It was great. We stayed in the factory

for two days and by the time we left we were glad to

go. It was hot and everyone dried out. The rumor

was that we were heading for a railroad that would

take us to southern Germany, to another stalag. The

place that was so nice and warm when we arrived soon

become just what it was built to be, an oven. It

was hot and dry and we forced open as many windows

as we could and broke a few just to get some air to

breath.

As we formed up into columns to continue the

march the German food ration showed up. A chunk of

ersatz bread and a chunk of bloodwurst sausage was

issued to each man. The first German food since the

march began. About noon we heard the start of a

constant rumble of muffled explosions. Berlin was

fifty or sixty kilometers north east of us now and

this must have been a mighty big raid ‘cause it went

on for what seemed like hours. You could tell it

was affecting the morale of the German guards. They

didn’t talk but lowered their heads and looked at

the ground. They were probably ready to cash it all

in, but still had their jobs to do. Before dark you

could see the smoke from the bombing.

We came to a town called Graustein where we were

to spend the night. It had warmed up a lot and the

snow was melting and rain was adding to the

discomfort. They had a time finding enough barns

for us to stay in but somehow most everyone had some

kind of cover if not in barns then in chicken

coops. Unfortunately there were no chickens or

eggs.

At dawn we moved out again, heading west this

time. Around noon we came to the town of Spremberg.

We marched to a German army post and were told to

fall out and relax. The post was extremely well

fortified with artillery and many tanks. They also

served up a huge pot of some kind of thick barley

soup, nothing like the watery stuff we had back at

Sagan. They even furnished some water for shaving.

Not all of us got the hot water, but the colonels

and the general did. The rumor was that the

general, colonel Spivey and a couple others were to

be sent to Berlin. The rest of us were to board a

train heading for the south of Germany.

We had to march about five kilometers to the

freight yard to board the train. We were put into

French forty and eight freight cars, so named

because the French designated them for forty men and

eight horses. Following typical German thinking,

fifty men were shoved into each of about forty cars,

and the doors were barred from the outside.

Traveling in these freight cars was worse than

walking in the snow. There was not enough room for

us to sit or lie down even after hanging all our

packs on the walls and from the ceiling of the car.

Some of us tried to use our blankets to make

hammocks swung across the car so that others could

sit or lie under us. It worked for a while, but

eventually someone’s knot would come untied and he’d

fall on whoever was under him. It was funny as

hell, but for the guy on the bottom it was no joke.

There were two window/vents in the car, one at each

end. We tried to have a man who could read German

posted at each so that he could see where we were

going and read any signs indicating the towns we

passed. We had a bucket that was supposed to be

used as a urinal, and it was passed from man to man

as needed. When it was half full it was passed to

one of the guys at the window who in turn emptied it

out the window. That was a trick in itself, since

the first time it was tried a lot of it came back

into the car. Not being able to stretch one’s legs

every once in a while without making someone else

mad was impossible. Somebody could find humor in

just about everything that happened and I think that

kept us going, but the grumbling and bitching

continued during the whole trip.

After about twenty four hours or so the train

stopped at Chemnitz, and the doors were opened and

some bread and margarine was slipped in. There were

four German guards with ready rifles standing about

twenty feet away aiming at the doors as they were

opened. We were not allowed to get off. The stop

must have taken about fifteen minutes and we were on

our way again. About noon the next day we stopped

just outside Regensburg and were allowed to get off

the train for a toilet stop. There were no

facilities so every man found his own space and

relieved himself for the first time in forty eight

hours. The fields and ditches along the track were

dotted with men squatting with their coats up over

their heads oblivious to the many German civilians

watching from across the tracks.

We were herded back into the cars after about

thirty minutes, and six hours later arrived at

Moosburg. Our cars were left on a siding and we

were forced to remain in them for another night.

All night long we pounded on the doors and shouted

but nothing happened. It was like we had been

forgotten, and the imaginations ran wild about what

the future would bring.

Next

Chapter 1:

Barksdale Field

Chapter 2:

England

Chapter 3:

Captivity

Chapter 4:

Sagan

Chapter 5:

The March

Chapter 6:

Moosburg

Chapter 7:

Liberation

Accueil

Rapports d'évasion

Articles

Recherche historique

Contact

Liens externes

Conditions

générales

Politique

de confidentialité

Home

Historical Research POW

Evasion

Reports

Contact

External Links

Terms and Conditions

Privacy Policy |